Canada in the Post-Pandemic World

Global events like pandemics produce permanent changes, and Canada needs to reimagine its role in a changing world. Reaffirming a commitment to our values requires a paradoxically muscular idealism.

Some of you have asked me to do a newsletter at some point on foreign policy, so that’s what I’m going to do this week. I don’t think the argument here is particularly original, but I found this a useful exercise for myself to craft a sort of manifesto for what a post-COVID Canadian foreign policy could look like, hopefully you’ll find it interesting.

Foreign policy doesn’t tend to get much of a look-in by the Canadian electorate. One of the reasons for this is that for decades now we’ve had the luxury of apathy. Foreign policy and Canada’s role in the world isn’t something we’ve had to put much thought into or have big electoral battles over because it really hasn’t mattered all that much. Yes, we’ve still had to make decisions about how we approach foreign relations and how we behave in the international arena, but the truth is that in the post-war, and especially the post-cold war era, we’ve never really had to think all that much about our role in the world beyond vague idealistic notions and commitments.

But the world has changed a lot in the last few years, and especially this year. Global events like wars and pandemics tend to produce permanent changes, and the world is going to look very different on the other side of the pandemic. We’ve got to start seriously thinking about what our role is in this new world.

This present both a challenge and a genuine opportunity for Canada. The Liberals have dominated our self-understanding, and reputation on the world stage for decades, and built our foreign policy around an idealistic commitment to multilateralism. This approach is obsolete, and we’ve got to rapidly reimagine ourselves to adapt to an already changed world. If Canada’s want to remain a champion of a rules-based international order, which we should, our approach needs to change.

This also presents a real opportunity for the Conservatives, I think, and they could potentially be the champions of a new 21st century foreign policy that renews an idealistic commitment to a rules-based international order. Paradoxically, I think we actually have to simultaneously become more idealistic in order to become more realistic. In order to protect and defend democratic values, we have to take a more confrontational approach and be willing to put up more barriers to nations that threaten and don’t buy into a rules-based order. To defend our ideals we have to get tougher.

The End of Unipolarity

The collapse of the Soviet Union ushered in what the late Charles Krauthammer, in a famous Foreign Affairs essay, called the “unipolar moment” in which the United States became the unquestioned global hegemon, with no true political, economic, or ideological rivals left. We have been living for the last three decades in this moment.

But Krauthammer’s use of “moment” is deliberate. Krauthammer readily admitted that unipolarity was temporary, and that “no doubt, multipolarity will come in time.” Were he alive today, Krauthammer would probably be ready to proclaim the unipolar moment over. Great power rivalry is back, and the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated this, killing off any hopes that the relationship between an increasingly aggressive China and the United States could be anything other than adversarial.

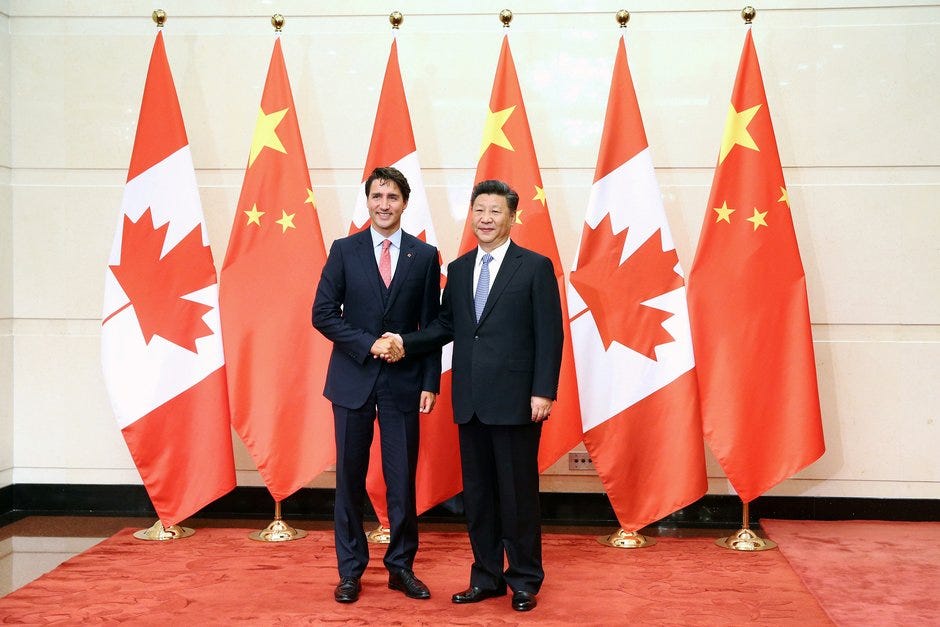

This rivalry looks set to become the defining feature of the post-COVID international order, and as the Meng Wanzou case and the kidnapping of the two Michaels reveals, Canada finds itself unavoidably caught in the middle of this burgeoning rivalry. Where Canada fits into this is now one of the most important questions facing our country today.

Canada’s relationship with the United States is our most important relationship. We are unavoidably connected to our neighbour, and our relationship with the United States is a largely amiable one. But despite our integration and close ties with America, Canada remains a sovereign nation, and most Canadians retain a desire for Canada to continue to behave and act like one. Similarly, while it is a Canadian pastime to criticize the flaws and failings of our southern neighbour, we still share the same fundamental democratic values. Thus when it comes to figuring out where Canada stands in the middle of this new great power rivalry, we have little choice but to be broadly aligned with the United States and other free democratic nations.

Retaining Our Sovereignty

That does not mean however, that Canada should simply become a willing American vassal in this conflict, and in the face of a rapidly changing international landscape, Canada must carve out a new role for itself to ensure we remain an independent nation. We must be an American partner, not vassal.

This is increasingly important given that America looks increasingly unreliable and ambivalent about its global commitments. This wouldn’t mean abandoning or ignoring relations with America, that would simply be impossible. But it does mean renewing our efforts to strengthen and build both bilateral relations with other nations, and multilateral relationships and agreements with nations that include the United States. It also means strengthening and renewing our own union and confederation.

Canada can accomplish these goals by prioritizing the strengthening of our relationship with other democratic nations that share our values and are also wary of the rise of an aggressive China with global ambitions. There is no shortage of other nations that fit this description. Most obvious are other Commonwealth nations with which we share common values and history. I’ve written before here in defence of CANZUK, a proposed agreement between Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom that would strengthen economic ties and prioritize foreign policy and military coordination between these four nations. This is a good start, and strengthening the relationship between other Westminster nations to ensure that we all have an independent voice alongside America would be valuable to all prospective CANZUK members. O’Toole was an early supporter of CANZUK during his 2017 leadership bid, and this is something we should prioritize.

Another Commonwealth nation that Canada should prioritize the strengthening of economic and political relations with is India, a nation also threatened by an assertive China. While Canada-India relations have soured under the current government, rebuilding this relationship should be a priority. The current Indian government is not without its controversies and diaspora politics in Canada is complicated to put it mildly. But in the face of a confrontational and dangerous Chinese regime, we don’t have much choice other than to pursue closer and warmer relations with India, even if this will displease some.

Strengthening these international alliances and relationships simultaneously allows us to pursue a foreign policy independent of the United States, while also allowing us to remain committed to democratic values and a rules-based order alongside America. Both positive outcomes.

We Cannot Divorce Economics from Politics

While some pundits and analysts have begun referring to the US-China rivalry as a “Second Cold War” the analogy is not quite perfect. As Sean Speer points out, “The West and China are much more economically integrated than was the case with the Soviet Union.” This makes the necessary decoupling of Western economies from the Chinese economy a very difficult and challenging task.

This is why decoupling cannot simply involve a retreat into economic protectionism and isolation, but the strengthening and deepening of economic ties with reliable partners. Commonwealth nations are one avenue for this, another is to continue to strengthen the ties with Pacific nations. The new Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which was the successor to the Trans-Pacific Partnership that President Trump withdrew the United States from in 2017, is an important piece in this puzzle, because it strengthens economic relations based on a rules-based trading order around the Pacific that excludes China. It is simultaneously a trade, and geostrategic agreement. These economic relationships will be vital going forward if serious decoupling is going to take place.

But a long term strategy to deal with Chinese aggression should include supporting alliances and organizations designed precisely to do this. The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QSD) established between Australia, India, Japan and the United States, is one such informal group, with the aim of establishing an “Asian arc of democracy.” These are exactly the agreements and discussions Canada should support and prioritize. Britain has proposed something similar that it is calling the “D10” focused specifically on telecommunications security, and will attempt to establish cooperation to build alternative suppliers that can create 5G infrastructure and technology to reduce reliance on Chinese companies like Huawei. In an area like telecommunications, economic and security considerations are inseparable, and groups like the D10 will be a vital part of both strategic and economic decoupling.

The broader lesson, and foundational assumption that we need to (re)learn here however, is that we cannot divorce economics from politics. When we pursue closer economic ties and integration with other countries, politics is part of the equation. That economic power is essentially political power is something the Chinese government fully understands, but it is something we in the West appear to have forgotten, and need to rediscover. Fast.

Just as an idealistic commitment to democracy requires a kind of hard realism in recognizing who our allies and who our rivals are, a commitment to markets actually requires a recognition that we cannot treat countries that play by the rules and countries that don’t the same. We should actively pursue closer economic relations with other countries that share our commitments in this new world, not with countries that don’t.

Muscular Multilateralism

In addition, Canada should not abandon, but recommit itself to supporting and strengthening the international institutions that we have a long and storied history of championing. The pandemic has exposed how many of these organizations, like the World Health Organization, have been co-opted by China, and while the American solution appears to be to simply abandon these organizations, Canada should instead lead the way in reforming these institutions to prevent them from becoming extensions of Chinese power. In doing so we can enhance our independence on the global stage by stepping up while America steps back.

Strengthening these bilateral and multilateral commitments does not mean reducing cooperation with the United States, it enables us to exercise an independent voice while remaining broadly and closely aligned with our neighbour. It also ensures that the coming era in which globalization appears to be in retreat is not one defined by “Canada alone,” it is one in which we remain open and committed to a liberal order.

The global pandemic is the closing act of the unipolar moment, and while it has become cliche to say that “this is the new normal,” it is now impossible to ignore the return of great power politics. The next few decades look set to be defined by this new rivalry, and Canada must think seriously about its role in a changing world. Canada can and must remain a champion of democracy and an open, rules-based international order, while also remaining independent from our southern neighbour. It would be wrong to see this moment as an opportunity, but Canada can and should use this new world to champion democratic values, while finding ways to continue to act and assert itself as an independent player on the global stage.

Weekly Recommendations:

It’s a few years old, but I’d highly recommend this address given a few years ago by Justice Glenn Joyal, the Chief Justice of the Court of Queen's Bench of Manitoba on how the Charter has transformed Canadian political culture. It’s a brilliant address, and Justice Joyal is one of Canada’s finest legal minds.

While on the topic of Canadian jurisprudence, I’d encourage you all to check out, if you haven’t already, the blog Double Aspect run by Leonid Sirota and Mark Mancini. Both Leonid and Mark are brilliant minds, and while I don’t think Leonid is a huge fan of me or my politics, Double Aspect consistently produces lots of really good and informative analysis. They are both excellent scholars.

I’ve been catching up this week on lots of reading and listening that I’ve fallen behind in because of academic commitments that are now mercifully done. I highly recommend the History of Ideas series that has been produced by the well known and UK podcast Talking Politics. The episodes on Constant, Arendt, and Weber are especially good and if you don’t know much about these thinkers they are great introductions.

Rules based order is just a euphemism for the double standard between developed & developing spheres.

Thankfully, it's behind us||

Definitely some good potential options! I think indecision and waffling especially get penalized in the sort of environment we seem to be moving into. Plenty of ways to actually engage and gain on Cdn priorities, provided we pluck up the political willpower. I think that's the principle thing, beyond perhaps a good strategic understanding of the world, that we seem to lack since the Cold War...